I miss being able to concentrate on a movie.

It was such a natural part of my life. From the age of 6 or 7, when my parents would use the movies as a convenient babysitter, to well into my 30s -- I’d go to a theater twice a week and unwittingly train myself to enter the dream state. That’s what movie-watching is, the closest we come to the cinema of our unconscious. Dreams are the most sophisticated storytelling engines we have, full of cuts and point-of-view shifts and a wild flip-flop of abstractions and literalizations. Movies aspire to, but never quite reach, this level of virtuosity.

But oh man, when it gets close! It has the force to become part of your personality. I’m thinking of a few of the movies I saw as a teenager — The Piano, The Crying Game, Fargo, Clueless, The Usual Suspects, Election, The Fifth Element — all of which I watched several times in a theater and would deeply affect my writing and sensibilities to come. What was crucial to this influence though was my attention. When I went to see a movie, the phone wasn’t a thing. Either literally (I didn’t get my first until the early 2000s) or later, because the screen was just too big and immersive to compete with any interest in a smaller one.

Movies are different now. The ones in theaters are machines more than films. Factory-built automations directed by algorithm. Which leaves the kind of movies I love and grew up with — the weirdo, arty, idiosyncratic ones — to fight for attention in the jungles of streaming. And when I do find them…

My attention doesn’t win.

Not like it used to.

My phone. My damn phone!!!

Every few minutes, I’ll pause the movie to check my texts. Or take a phone call. Or get blueberries or corn chips or Honey Mama’s while I surf Instagram.

The movie has become the dreaded second screen. I don’t know how. It just happens. I’m no longer dreaming or committing to flow state. I’m committing to distraction.

Maybe I’d be less distracted if the movies were better, I think smugly. But the better ones seem like too much work, and you end up choosing the sundrenched, breezy rom-com set in Italy, with zero conflict or escalation and everyone in skimpy bathing suits, just because it’s easier to watch while distracted — the quality of the films and the quality of our attentions in some demented feedback loop.

The new gen doesn’t even have the old ways to remember. When I talk to my nephew or niece on the phone, they’re simultaneously talking to me, texting me photos of whatever we’re talking about, playing video games with friends, snapchatting about how badly they’re beating someone in said game, and loading up their homework on another screen just so it’s in their peripheral vision.

Both my niece and nephew are wonderful readers, but still, I wonder whether reading is fundamentally a different experience than it used to be. Because a book isn’t a great second screen — not like a movie or video game or FYP page loaded with dopamine hits. It requires immersion and commitment and the desire to enter that dream state with the author. It is, at its heart, a very, very intimate experience. (I still feel strange that The School for Good and Evil was ever published, because the whole thing felt so… personal.)

But what if we can’t expect that same level of intimacy and commitment anymore?

Then we better have some novel strategies to keep a reader reading.

Here are some of mine.

1. Know Your Strength

Every writer has a different core strength. I went to Anne Rice for the sensuality of the prose, Patrick Dennis for the campy comedy, Alan Hollinghurst for the depth of emotion, Gillian Flynn for the puzzle pieces. Knowing your strength — your calling card that elevates you and draws in your particular breed of fans — helps you lean into it and deliver on what your audience wants. Even if you make a big swerve in your career, like I have, and are experimenting with new form and genre, that special sauce still needs to pour over.

In my case, I think my greatest strength is pace. The feeling that you can just pull open one of my books and tear through it.

Interestingly, though, this sense of pace changes with the times. In 2013, The School for Good and Evil was considered rip-roaringly quick. Some reviewers quibbled with the relentlessness of it and how much happens in 100,000 words. But it also made the book highly accessible to reluctant readers and tempted ones who were previously allergic to books to give this one a chance.

But now, more than 10 years later, The School for Good and Evil is no longer a fast book. In fact, it’s considered downright literary and reluctant readers are increasingly terrified of a book that has so many words on the page instead of pictures.

All that to say — as the definition of pace changes, and the thresholds of pace that hold a reader’s attentions, my writing has to change with it. 2013 speed does not equal 2024 speed.

So how do I adjust?

2. The Fast Fly Draft

Early in the writing of a novel, when I’ve drafted about half of it, I take a break from generating new material. I load up the whole book in Focus View on Microsoft Word, which blocks out distractions, and I read it straight through from start to finish — without taking a break or even letting my eyes pause. Essentially, I read it double-time, like I’m in a mad-rush or cramming for an exam.

All the while, I’m monitoring my internal metronome. Every time I get bored, feel like I’m dragged down, or get lost in words, I highlight the sentence in yellow. At the end of this process, I then spend a few days working exclusively on those highlighted passages. No matter how much I like these parts, I know there’s something wrong with them, because they didn’t survive the Fast Fly Test. Most of the time, I delete the highlighted phrases completely. Or at the very least, hack down the number of words. This is how I managed the first 6 SGE books and was able to maintain such a quick pace to the books, while juggling 120 characters and more than 70 different plot threads.

But about 2 years ago, while writing Rise of the School for Good and Evil and Fall of the School for Good and Evil, I added a new step to my Fast Fly Draft.

After Fast Fly Test #1 in Focus View, I do a Fast Fly Test #2. This time, I read the book on my phone. Not only that… I read it on the small screen while walking.

Usually, it’s in Forest Park in St. Louis, where no one’s around much during the day. I read as I amble, marking any sentences where I get stuck or bogged or lulled into losing my place. Yes, it’s a tall order – the screen is small, I’m sweating through my shirt, I’m distracted by squirrels and runners and cravings for snacks – but that’s the point. The book needs to hold me. Every word of it. And anything that doesn’t gets the dreaded neon mark. Later, I deal with these sentences like suspects in a crime and either reform or exile them.

The end result of all this is faster speed, without sacrificing the quality of the story. I believe JK Rowling used to do a version of this with the Harry Potter novels — in fact, she notes that during the writing of Book 5, she got so tired that she didn’t do her usual pacing draft, where she hews a book down to its essentials, which is why Order of the Phoenix is so unusually bloated.

In the new novel I’m writing, I’ve already done the Fast Fly Test six different times. This book is designed to be a muscular speed-machine that hooks in and doesn’t let you go. Which means finding the pace of it is as integral as locking down the plot and characters. After 6 tries, I think I’ve found it. But I’ll probably test again in a few months…

3. Don’t Be Afraid of AI

I got my start in writing as a screenwriter/director, so I think cinematically, often doodling scenes in my book with stick figures first, so I can sort out the action and points-of-view. Especially in this new novel, where I have scenes featuring up to 20 (!!) significant characters interacting at a time, I need to have a super clear sense of movement and flow.

Pre-viz – or computerized storyboarding – is an important part of movie-making. For The School for Good and Evil movie, nearly every big action scene was pre-vized ahead of time to figure out the shots and save time during filming. (Think the Pumpkin Reaper chase during the Trial by Tale; every single one of those shots is pre-designed.)

Which got me thinking: can I pre-viz for a novel as well?

Here’s where AI can be immensely helpful. (I’ve spoken in a previous entry about the ethics and nuances around AI, which I’ll spare repeating here.)

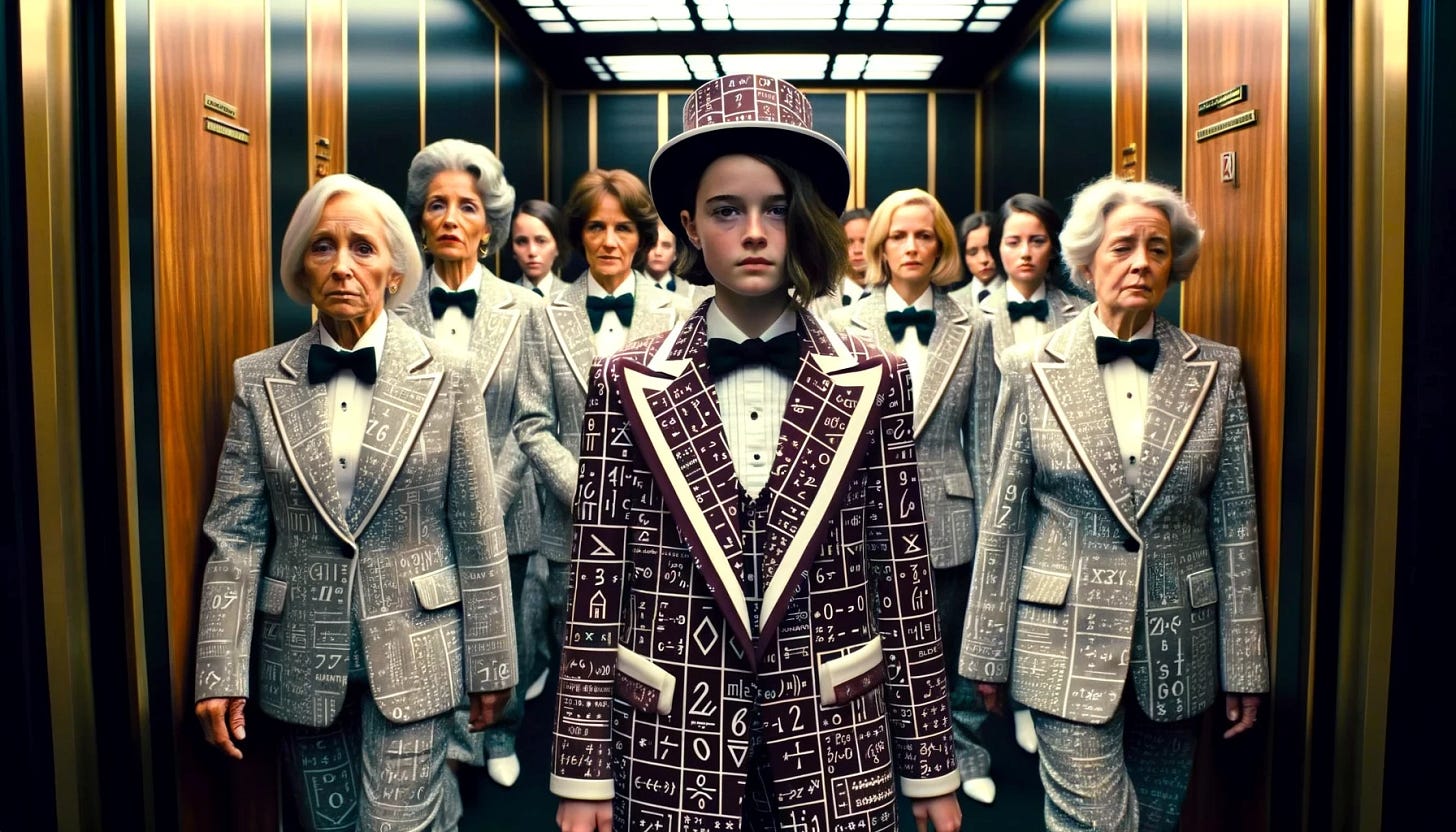

In one big entrance scene in New Novel, I have groups of teenagers arriving at a party, each cohort dressed and moving differently to help brand their vibe and personality to the reader. (Think the entrance of the various magic schools for the Triwizard Tournament in Goblet of Fire.)

In the old days, I would just write the scene and hope my visual branding is strong enough to imprint in the reader’s head. But now, after finishing a paragraph, I can test out translating it into visuals to see if what I’m describing actually comes through. For instance, in the middle of this big party scene, check out the variations of one group’s entrance, based on the small tweaks and revisions I made to a given paragraph:

I’ll leave it a mystery as to who this is, what she’s doing, and which version I ultimately went with, but seeing the images come alive in an AI generator — a lightning quick version of pre-viz — helps me tweak my revisions and be increasingly objective in how a reader might perceive the details of my language. All of which is immensely important in heightening the clarity and precision of my writing at a time where both these things are paramount to keeping a reader’s engagement.

I’ll share more strategies with the New Novel as I get closer to announcing it, but for now hopefully these give you a sense to how my own writing is evolving to keep up with the changes in how we read.

Do you read differently than you used to? What do you notice about what’s important to you as a reader now versus a few years ago?

Until next week…

I just went to an AI panel at a writers conference and they touched on using it in this way. I'm excited to try this!

And now I think I'm wondering what my strength is. I think it might be earnestness.

I just thought authors hoped their books read fast and their writing style is fueled by caffeine, I totally didn’t think that you can use techniques like the Fast Fly method. This insight is definitely something that won’t be found in a typical writing book!